Will Elementary Science Remain the Forgotten Stepchild of School Reform?

Great science standards can help schools accomplish great things, but only if those schools spend time teaching them. That may sound like a truism, but that simple fact could hamstring efforts to improve science education across the country.

Change the Equation dug into survey data from the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) for fourth-grade science and found that many of the nation's elementary school children were on a starvation diet of thin and infrequent science instruction. Elementary teachers received precious little professional development in the kinds of science instruction favored by new science standards adopted by dozens of states, including the Next Generation Science Standards.

If these conditions do not change, the new standards may not fulfill their promise, and states may squander a vital chance to give children a strong foundation for achievement in middle school science and beyond. 1

Fortunately, states can adopt policies to encourage much more robust science teaching in elementary schools. By including elementary science in their school accountability systems and supporting better professional development, they can counter the forces that drive science out of elementary classrooms.

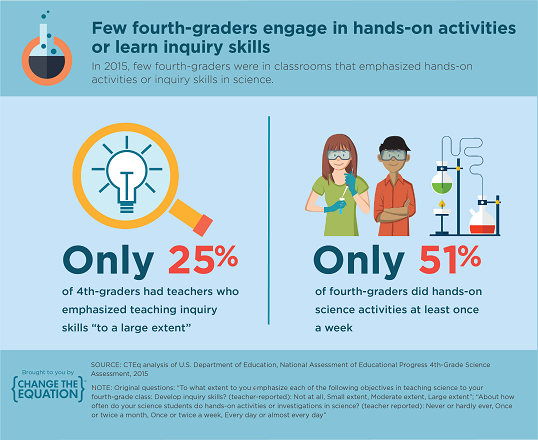

Hands-on, inquiry-based science is scarce in elementary school

Only about half of the nation's fourth-graders do hands-on science activities at least once a week, and only one in four have teachers who focus on inquiry skills:

To put it bluntly, most fourth-graders don't experience very good science instruction. (And, as we'll see later, their teachers aren't really to blame.) Decades of research support the value of hands-on science experiences that develop students' ability to engage in sustained scientific inquiry. In fact, that research informs the "animating vision" behind the Next Generation Science Standards, which aim to transform science education in states across the country. That vision is still far from reality.

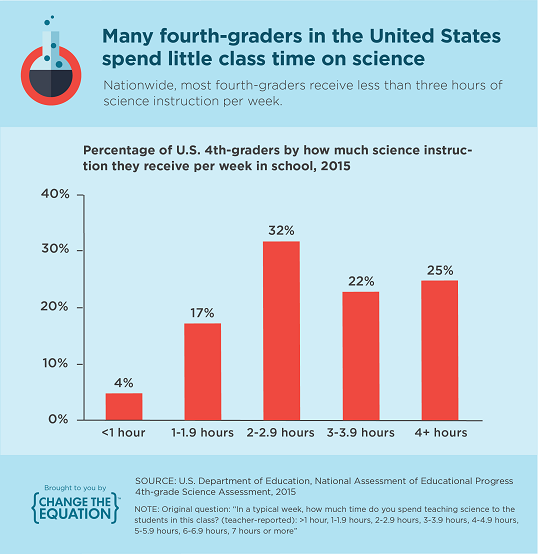

Few elementary students spend much time on science

One major constraint on elementary science is time. Students who spend little time on science will have less exposure to hands-on, inquiry-based science.

Unfortunately, time for science is a scarce commodity for most U.S. fourth-graders:

Most U.S. fourth-graders spend less than three hours a week in science - and one in five don't even get two hours. A mere 14 percent spend at least five hours a week, or one hour a day, on science. In 12 states, at least two thirds of students fall below the three-hour threshold (To learn where your state stands, visit our Vital Signs website and select your state from the drop-down menu.)

How much time is enough?

Those looking for ironclad consensus on just how much time elementary schools should spend on the subject will look in vain, but few would consider three hours a week a very ambitious target. The National Research Council advises schools to provide enough time for "sustained investigations," 2 and notes that "opportunities to engage in the practices of science require ... more time than the 30-45 minute session that elementary schools typically allocate to a science lesson."3

After all, children need time to define problems, carry out investigations, analyze data, explain results, design solutions — all priorities inscribed in the Next Generation Science Standards. Children cannot develop scientific habits of mind on the margins of the school day.

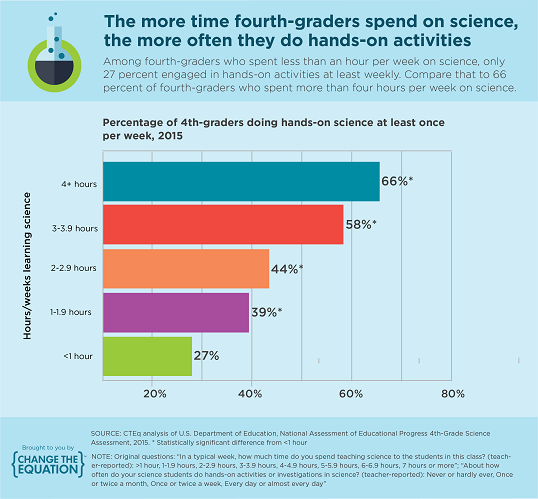

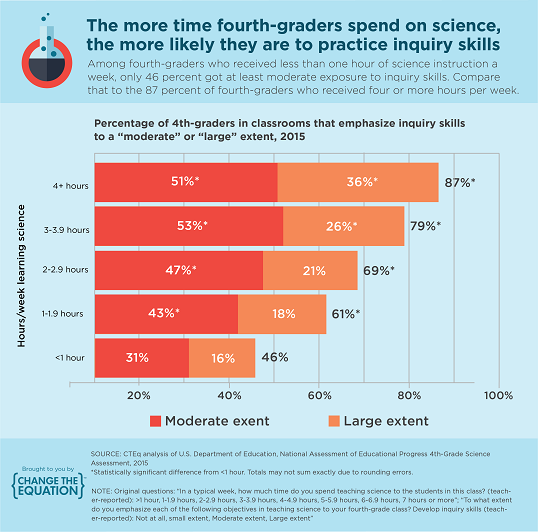

Expanding time for elementary science can make a difference

Time is no panacea, but it does clear space for better science teaching. The NAEP data we examined bear this out.

Students who have more time for science in school are more likely to do hands-on activities: 4

Their teachers are more likely to emphasize inquiry skills:

And it should surprise no one that they also tend to earn higher science scores on NAEP:

No, time alone will not work miracles. If it did, rising time for science would prompt even faster gains in scores. Still, the evidence points to time as a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for student success.

When and why did elementary science become a forgotten stepchild?

States used to recommend more time for science. As far back as 1986, states commonly counseled schools and elementary teachers to devote a minimum of 175 to 225 minutes per week to the subject. Teacher surveys at the time "suggested" that the average teacher cleared the lower bar, spending roughly 190 minutes on science.

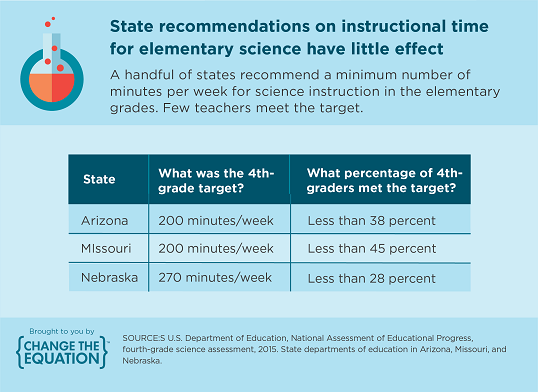

How times have changed. The few states that still make recommendations set the minimum bar higher than three hours, but these days those recommendations are about as binding as a New Year's resolution:

Beginning in the late 1980s, states ramped up pressure on schools to lift students' performance in reading and math, while science tumbled down the priority list. The 2002 No Child Left Behind Act codified accountability for reading and math results in federal law, before The Every Student Succeeds Act replaced it in 2015.

One national teacher survey found that, between 1994 and 2008, the average time for science in grades one through four fell from 3.0 to 2.3 hours, before rebounding somewhat to 2.6 hours by 2012. 5 Early in the new millennium, school and district leaders attributed similar trends to No Child Left Behind.

Another reason for the elementary science drought: scant support for teachers

Teachers who aren't confident in science are probably not inclined to spend much time on it. Many elementary teachers would be among the first to admit self-doubt when it comes to science. In a 2012 survey, only 39 percent said they felt "very well prepared" to teach science.

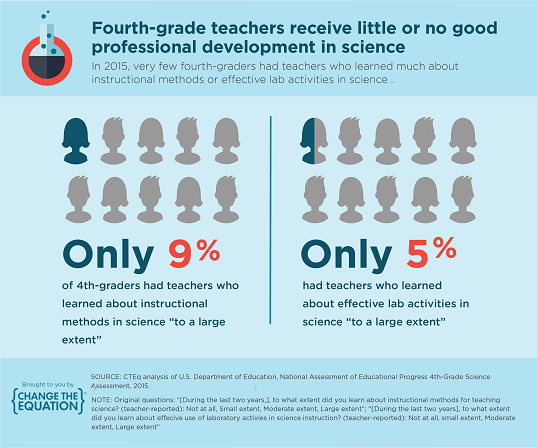

Small wonder. Few receive much professional development:

Such lack of support for elementary teachers compounds another problem: few have a strong background in science to begin with. In 2012, only 36 percent of K-5 teachers said they had taken courses in all three of the areas the National Science Teachers Association recommends for every elementary teacher: life, earth, and physical science.

Lack of accountability for science may fuel this dynamic as well. Districts and schools have little incentive to spend precious professional development dollars on elementary science as long as the subject does not count in any school performance ratings.

A tale of two states: making elementary science a priority in schools

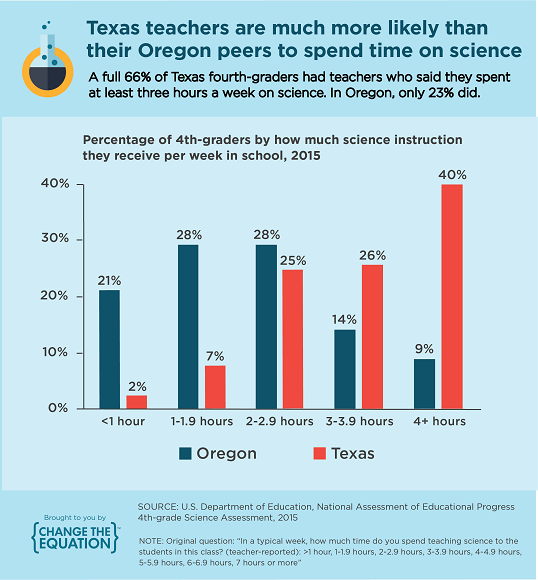

The good news is that states can have a dramatic impact on the amount of time elementary teachers spend on science. The difference between Texas and Oregon is instructive:

What is Texas doing that Oregon isn't? Unlike Oregon, Texas makes elementary students' performance in science count towards schools' overall accountability ratings. (Schools in states that do so generally devote more time to science.) 6 In addition, its elementary teachers are much more likely to receive professional development in science. 7

Both options for bringing elementary science back into the fold are within every state's grasp. As states submit their plans for holding schools accountable under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), they have the option to add science to the list of indicators on which they will judge schools. States can also provide funds for professional development in elementary science.

It is too early to tell how many states will follow this path — their ESSA plans are still rolling in — but Oregon is making some promising motions. The state's draft plan says state leaders will consider "including science in the accountability system" after its new science assessment launches in 2018. It also cites the state's STEM plan, which explicitly aims to boost "time for inquiry-based science" to "at least 3-4 hours per week in elementary school."

The national data on elementary science may look grim, but advocates for science education should still take heart. As more states adopt new science standards that focus on inquiry and build new science tests to match them, they may yet create more incentives for elementary teachers to teach science especially if advocates continue to make the case.

Post-script: Take advantage of afterschool!

The troubling data on elementary science should also fan the flames of afterschool advocacy. The fact that millions of children get such a thin diet of science at school provides ample reason to support hands-on science outside of the school day. Research by The Afterschool Alliance finds that millions of U.S. children would participate in afterschool programs if such programs were available to them. At a time when so many elementary schools neglect science, afterschool offers a largely untapped strategy for fueling children's interest in the subject.

*Updated on 5/9/2017 to correct the percentage of teachers who said they felt "very well prepared" to teach science.1 Decades of research hold that elementary-age students can grasp sophisticated concepts and practices in science. Surveys suggest that many scientists choose to pursue the field by middle school or even earlier.

2 National Research Council, Framework

3 National Research Council, Monitoring Progress Toward Successful K-12 STEM Education: A Nation Advancing? https://www.nap.edu/read/13509/chapter/1#iv.

4 These and other NAEP data in this report do not prove causal relationships or tell us about the direction of cause and effect, but they do suggest a logical story. Hands-on activities and sustained inquiry take time, and so do the kinds of teaching that improve students' performance.

5 U.S. Department of Education, Schools and Staffing Survey, 1994-2012.

6 Eugene Judson, The Relationship Between Time Allocated for Science in Elementary Schools and State Accountability Policies, Science Education, 97 (4), 621-636. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sce.21058/abstract

7 Fifty-four percent of Texas fourth-graders had teachers who, to a "large" or "moderate extent," received professional development for instructional methods in science. Only 15 percent of their peers in Oregon had such teachers. Forty percent of Texas fourth-graders had teachers who, to a "large" or "moderate extent," learned about effective lab activities in science. A mere six percent in Oregon did. (National Assessment of Educational Progress fourth-grade science assessment, 2015.)

© 2024 by the Education Commission of the States (ECS). All rights reserved. ECS is the only nationwide, nonpartisan interstate compact devoted to education. P.O. Box 33674, Northglenn, CO 80233

To request permission to excerpt part of this publication, either in print or electronically, please contact the Education Commission of the States’ Communications Department at 303.299.3636 or mboatenreiter@ecs.org.

Your Education Policy Team www.ecs.org